|

Come with me now to Greenwood, South Dakota, where in my heart still live the carefree, wondrous days of early childhood. Slip through the rushes and cattails to the water’s edge and peer south across the Missouri River to the Nebraska shore, more than a mile distant, where red sandstone bluffs, cloaked with cottonwood and box elder, rise hundreds of feet from the water.

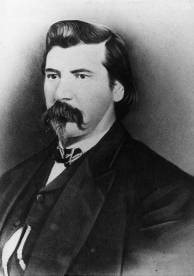

It took a mighty river to cut this deep, wide canyon through the stone. The Missouri was a mighty river—until the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers dammed it at Fort Randall, twenty miles upstream, in 1956. Above that dam today is a long lake where people swim, sail, fish, and otherwise entertain themselves. Below the dam, the river is shallow and languid. Sandbars and islands, once wiped bare by spring’s annual deluge, are covered with brush and trees. Many are dotted with small homes and cabins. The river is tame now. But when I was a boy, the Missouri ran wild and free. My mother’s father told me then that in his grandfather’s time, our people were as free as the Missouri. On a sea of rolling grassland stretching a thousand miles east to west and another thousand north to south, we roamed as we pleased, raising our children, living our lives in total harmony with nature, a sovereign people worshiping Wakan Tanka, the Great Mystery, who created everything and put us here to live on our Grandmother, the earth. My own mother, Theodora Louise Feather, was raised here on the Yankton Sioux Reservation. Greenwood, a river port, was the site of an Office of Indian Affairs (later called Bureau of Indian Affairs) agency, a location selected for its convenience to white officials who preferred to make their way by canoe and steamboat through the roadless Great Plains. Today, fewer than two dozen families remain in Greenwood, a few in modern double-wide “mobile” homes with satellite dishes in their yards, but most in old trailers or in smallish wood-frame homes. The biggest intact structure is a two-story church of red brick, with an incongruous rooftop battlement turret. The Presbyterian Church was consecrated in 1871; now it is used only for rare community meetings. The rest of Greenwood is a jumble of abandoned, crumbling dwellings, filled-in foundations, concrete slabs with grass struggling through massive cracks, open spaces with traces of the dwellings that once stood there. The large, circular masonry government buildings—built in a style still seen on reservations because BIA bureaucrats think it suggests our council lodges of old—are nothing more than ruins, roofs long ago collapsed under the weight of winter snow. Green things grow through paneless windows and doorless doors. Yankton is how whites say Ihanktonwan, which means “People of the End Village.” By ancient custom, when the nations of the Seven Council Fires assembled in centuries past, their lodges were pitched in an enormous circle, open at the east end. Ihanktonwan tipis always guarded the south side of the entrance to the great encampment, a position of honor. The grassy, gently rounded prairie hills descend almost to the river, nearly into what remains of Greenwood. Many Ihanktonwan are buried here, their graves unmarked, lost forever in a final, loving embrace with their Grandmother. You may deny the existence of ghosts or spirits, and I will not quarrel with you. But drop your gaze to this tall grass, raise it again to the vast skies, free all your senses to explore the moment, and it is hard to walk these hills without feeling a presence, something that cannot be explained by Euro-centric reasoning. On a knoll overlooking the river, rising out of chest-high buffalo grass, is a fourteen-foot gray granite obelisk. Its square base stone reads: To commemorate the treaty between the united states of America and the Yankton tribe of Sioux or Dakota Indians. Concluded at Washington D.C. April 19, 1858. Ratified by the senate, February 16, 1859. Whites inscribed this monument. What really happened was that several Ihanktonwan leaders were taken to Washington and kept there in hotel rooms for months under what amounted to house arrest. Finally, penniless, homesick, and confused by whiskey and grand promises, they agreed to cede millions of acres—their ancestral hunting grounds—to the United States, reserving in perpetuity only 430,000 acres for themselves and their descendants. In return, the “Yankton Sioux,” as the federal government insists on calling them, were to be paid an annuity, during fifty years, amounting to $1.6 million. Instead of cash, the government was to supply the equivalent in food, clothing, farm implements, livestock, and other necessities to make the transition from a hunting society to a farming nation. A U.S. agent would oversee distribution of the goods. The government also accepted responsibility for educating and providing health care to the Ihanktonwan. The President of the United States retained the option of reducing the annuity payments or suspending them entirely if the Yankton population happened to decrease—say, after one of the dozens of smallpox epidemics induced by the President’s agents after they distributed blankets infected with the smallpox virus, or if hundreds starved or froze to death because an agent had stolen their treaty goods. The treaty also provided that payments would continue for the annuity period unless “said Indians fail to make reasonable and satisfactory efforts to advance and improve their condition, in which case such other provisions shall be made for them as the President and Congress may judge to be suitable and proper” [emphasis added]. Advance and improve. Other provisions. Suitable and proper. Genocide. The Ihanktonwan treaty delegation was led by Padaniapapi, head of one of the seven councils, or bands, and spokesman for the Ihanktonwan Nation. Padaniapapi was born in a village on the banks of the Missouri about 1804. According to our oral tradition, on the day of his birth, the village had visitors—white men with Indian guides who had paddled up the Missouri on their way west, an expedition led by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark. Padaniapapi’s father, a headman, proudly displayed his newborn son to the white visitors. Lewis—or perhaps it was Clark—swaddled the infant in an American flag. Seeing him wrapped in the Stars and Stripes, Pierre Dorion, the French fur trader who acted as interpreter—and who doubtless spoke in a spirit of bonhomie—predicted that the child would become a loyal friend of the whites and a leader of his people. It would have been better for my people if only Dorion’s first prophecy had come true. As an adult, Padaniapapi became a mesmerizing orator who, it was said, could all but hypnotize an audience. His niece, Eagle Woman, married Honore Picotte, a wealthy French fur trader. In 1858 their son, Charles Picotte made his own deal with white land speculator J. B. S. Todd, first cousin of Mary Todd Lincoln. Then Charles set out to get the Ihanktonwan to make a treaty with the United States. First, he convinced his mother’s uncle that a treaty was in the Ihanktonwan’s best interests. Padaniapapi then spoke up to persuade his fellow headmen that that was so. When they arrived in Washington, Charles, the only member of the Ihanktonwan treaty delegation who could read English, thoughtfully provided barrels of whiskey to help his fellow delegates think more clearly. Making every effort at the treaty signing to accommodate the U.S. president, Picotte helpfully inscribed the marks of three headmen who had remained behind with their bands along the Missouri. For his services as “interpreter,” the United States gave Charles Picotte a 640-acre section—one square mile—of prime land. Speculator Todd helped him to develop the acreage into the town of Yankton, sixty miles east of Greenwood. Picotte became filthy rich. In public, he often lit cigars with twenty-dollar bills. He was widely admired by white settlers who flocked into South Dakota after the Yankton Treaty. Picotte, however, moved back to the reservation when he was forty-six. He gave away everything he owned to his poorer brethren, lived in the traditional manner of his Indian ancestors, and died a respected man among his mother’s people.

The other side of the Greenwood monument base plate reads: Delegates Who Signed Treaty Of 1858 Charles Picotte Jumping Thunder Mazzahetun Numkalipa Running Bull Walking Elk Standing Elk Bad Voice Elk Getanwokapi Hinhanwicasa In Memory Of The Yankton Chiefs Who Made The Treaty Of 1858. Struck by the Ree Black Bear Medicine Cow White Swan Crazy Bull Frank DeLoria Pretty Boy Feather In The Ear/ “Struck by the Ree” was what whites called Padaniapapi. When Padaniapapi was a young man, a Ree (also called Arikara or Padani) Indian had counted coup on his forehead during a skirmish. “Feather In The Ear”—the proper translation of his name, Wiyaka Na-pin, is “Feather Necklace”—was one of several headmen. When the other Ihanktonwan leaders departed for Washington, he was off on a buffalo hunt. When Padaniapapi returned from Washington with the treaty, Feather Necklace was among the headmen who met him. Even though they could not read English, Feather Necklace and the others knew a sucker’s deal when they heard one. They were outraged at those who had signed the treaty. In a melee between the treaty-making leaders and those who opposed it, Padaniapapi was wounded. More to the point, he was publicly humiliated. But we are a generous and forgiving people: Padaniapapi maintained his post as spokesman. And we are an honorable people: Even though no proper council had been called to discuss the treaty, our leaders had given their word, and the Ihanktonwan felt bound by it. And we are a peace-loving nation: In 1862, after our Santee brothers in Minnesota were robbed, first of their land and then of the food and other essentials pledged by their own treaty, they were told by arrogant white agents to eat grass—or their own dung. Facing starvation, the Santees rebelled and sent messengers to ask the Ihanktonwan to join them. The Ihanktonwan held out the hand of peace, keeping to their reservation and providing refuge for people fleeing the cavalry and vigilantes who, after the uprising, tried to kill every Indian in Minnesota. About two years after the 1858 treaty was signed, Dr. Walter Burleigh, the U.S. agent, was caught stealing many of the goods sent in payment of that year’s annuity. When Burleigh locked up all the hunting ammunition and refused to discuss the incident, Feather Necklace, along with several headmen and hundreds of people, surrounded the agency building and called for Burleigh to explain his actions. He refused to come out, so the Ihanktonwan gathered incendiaries and made preparations to torch the building. Only the timely arrival of heavily armed troops from Fort Randall saved Burleigh’s hide. In 1869, Feather Necklace led a movement to force John Williamson, a Presbyterian missionary, to leave the reservation. A deeply spiritual man, Feather Necklace spoke his mind in council. If the white religion were allowed to remain on the reservation, he said, the Ihanktonwan religion, which permeated every aspect of daily life, would be in jeopardy. Thus the tiyospayes—extended families, the foundation of our culture—also would be in jeopardy. “Let white missionaries live here, and soon they will tell us that everything we believe is wrong,” said Feather Necklace. Padaniapapi spoke eloquently on behalf of the missionary, but after everyone had had his say, the council voted to ask Williamson to leave. Nevertheless, Padaniapapi secretly offered protection to the minister. Williamson remained; the red brick church he built still stands in Greenwood. The Presbyterians were soon followed by Episcopalians, Baptists, Catholics, and several other Christian denominations. Within four years, everything Feather Necklace had predicted had come to pass. For the next 130 years, until the very moment I write these lines, his prescient prophecy has continued to be fulfilled. The missionaries of the various Christian denominations, each diligently trying to convert Indians to their own beliefs, disagreed over fundamentals of faith, including what the Bible really meant. But every sect wholeheartedly supported the U.S. government’s draconian efforts to eradicate Ihanktonwan culture. In 1881, for example, by Office of Indian Affairs fiat, our “keeping of the spirit” and “releasing of the spirit” ceremonies were outlawed. Those rituals began and ended our traditional yearlong way of grieving for the dead, family-and community-oriented rites that nurture Indian cultural values. About six years later, the sun dance—central to our worship of Wakan Tanka—was banned. Within a few years, all other sacred ceremonies were forbidden. Feather Necklace was among the hundreds who died in the smallpox epidemic—the white man’s plague—that decimated the Yankton Reservation in 1901. He was eighty-three years old. By that time, the BIA had decreed that, like whites, Indians must have single surnames, so on the official rolls, the names of Feather Necklace’s children were shortened to Feather. His son, the first John Feather, was my mother’s grandfather. The second John Feather was my own grandfather. I come from a long line of patriots. © 1995 Russell Means and Marvin J. Wolf Amazon Barnes & Noble iTunes Kindle Kobo Audiobook

1 Comment

Lisa de Vincent

10/24/2018 09:45:50 pm

WOW, love the writing so sad seems like nothing’s changed.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

FROM Marvin J. Wolf

On this page are true stories, magazine articles, excerpts from books and unpublished works, short fiction, and photographs, each offering a glimpse of my life, work and times. Your comments welcome. © Marvin J. Wolf. All rights reserved. Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

|

|

Member, Military Writers of America

|

Website © 2016 Marvin J. Wolf. All rights reserved on website design, images and text. ꟾ Updated regularly.

Design by Andesign. |

Professional Reader, NetGalley

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed