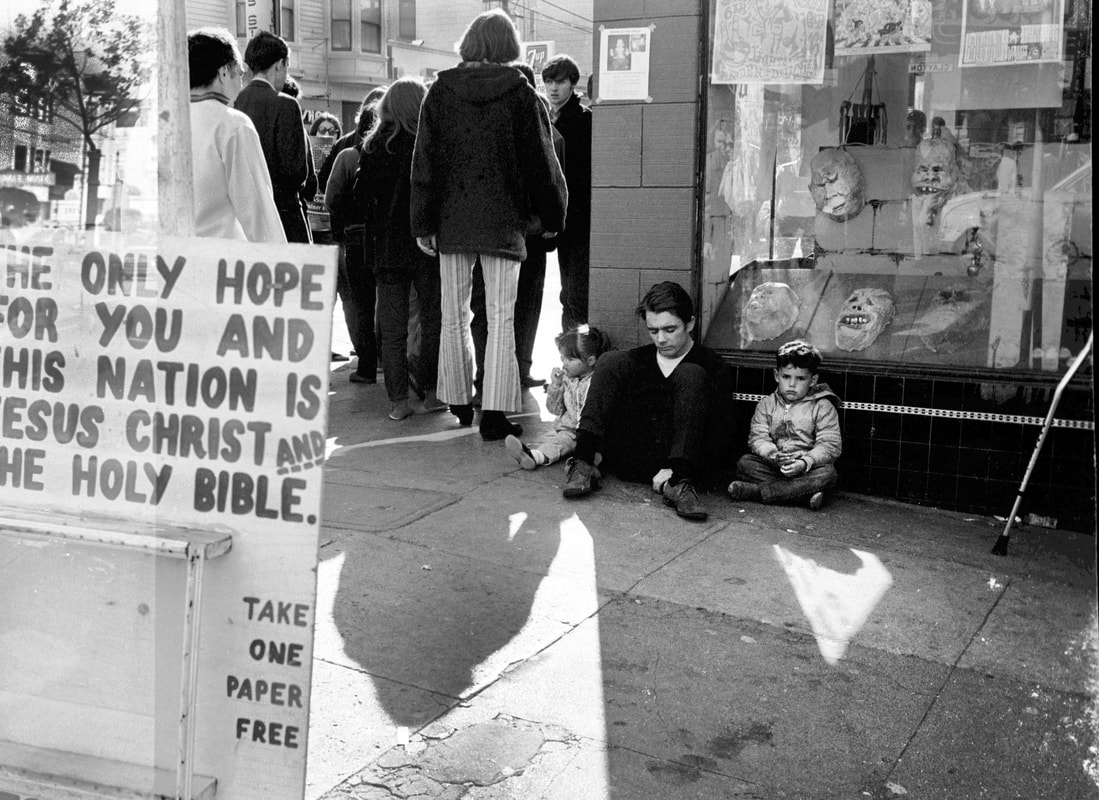

publicly confess their shortcomings, and to beg for God’s mercy. In The Pale of Settlement, it was long the custom for the rabbi himself to note both his own shortcomings and also to rebuke the most prominent men in his congregation. It is these prominent men who serve as the congregation’s leaders, and who raise the money to pay the rabbi and other employees. As one may imagine, rebuking these men is asking to be fired when a rabbi’s contract comes up for renewal. Having a noted maggid lead the services, deliver the sermon and rebuke the unworthy is therefore often advisable. This particular maggid had become widely known for the quality and intensity of his sermons. When he mounted the bimah, a raised platform in the synagogue from which he could address congregants, the maggid brought along a tiny silver snuff-box, which was far from unusual. As he began introductory remarks, he accidentally dropped the box, then surreptitiously kicked it under the Torah table, which was covered with an ornate cloth that reached almost to the floor. Turning here and there, looking for his lost snuff box, the maggid soon threw up his arms in exasperation, then turned to the congregation. “My snuff box is gone—it’s almost as if the earth itself has swallowed it… The rabbi’s expression changed, and he put aside the papers with his prepared remarks. “Swallowed by the earth! We must be reminded of Korah….” And the maggid was off on a rant about Korah, who in Exodus led a revolt against Moses and Aaron, and for this heresy was swallowed by the earth. Thus he created an opportunity to preach against the community’s wealthy and powerful, unsparing in his contempt, and faithful to the reason for his temporary employment. The following year, in another town, he would again lose his snuff-box and sermonize on the lessons of Korah. See? It’s not that hard. Thus I now attempt to connect two photographs, taken thousands of miles and many years apart: One of the most challenging skill sets taught in Army Basic Training is bayonet fighting. While we drilled in ranks holding our bayonet-tipped M1 rifles to practice the basic strokes of this ancient weapon, safely putting these skills into practice by fighting other men similarly equipped required replacing the bayonet with a thick pole with heavy padding on either end to simulate the bayonet and the rifle butt, respectively. This was called pugil stick fighting. On a grassy athletic field on a warm spring afternoon in 1959, our platoon stood in a circle. We recruits were clad in fatigues; we each wore padded gloves, a football helmet and an external diaper with a thick rubber groin protector. Two drill instructors moved behind the circle; each selected a man. On command, both fighters rushed toward the middle of the circle and mixed it up with each other, lunging and parrying. We were encouraged to be as aggressive as possible and to try to “kill” an opponent by driving the red-colored tip of our pugil stick into his chest. While so engaged, “butt” strokes with the other padded end of the stick might be used to stun or disable our opponent. A DI stood behind me, put a restraining hand on my shoulder, and whispered instructions in my ear. I was the shortest man in the unit, so he told me to use that, to stay low, lunge upward with my stick, making my strokes more difficult to parry. He added that a hard blow to my opponent’s shoulder or helmet with the butt end might disable him for long enough to stab him. Then a whistle blew and I found myself running headlong into the center of the ring toward a man I immediately recognized as my bunkmate. We were all sleep deprived, but Robert Paolinelli, occupant of the bunk beneath mine, kept me awake hour, maddening hour after hour with his deep, resonant snores. This was our third week of training, and other than asking him many times to do something about his snores, we had barely spoken. I hated him. Running right at him, my mind focused on what I had learned to do, and a desire to punish him for my lost sleep. I whacked him on the shoulder, and when he staggered backward, I brought the butt end of my stick up and caught him squarely under his chin. His helmet flew off. He went down. Instantly whistles blew and I backed away, suddenly contrite, and worried that I might have hurt him badly. Paolinelli suffered two cracked teeth. When I apologized to him, he laughed it off. We became best friends. He bought me my first beer. He invited me to meet his mother and sister, who lived in San Francisco. On our first weekend pass, I did, and his mother stuffed me with pasta fazool. Robert remained my friend for the rest of his life. We both left the Army in 1962. He took a job with an insurance company, and I sold books, and then cameras, and then, in March 1965, I re-enlisted. I returned from Vietnam on November 16, 1966 and took a bus from Travis AFB to San Francisco. As promised, Robert had left his key in a potted plant. While he was at work, I soaked in his tub for two hours, then collapsed on his sofa and slept. When he came home, we went out for dinner. I had packed civilian clothes before leaving for Vietnam, but when I opened my duffel bag saw they were terminally mildewed. Robert was a few inches taller and twenty pounds heavier, so wearing his trousers and shirt required some adjustment. But it was San Francisco in the Sixties. People dressed as they chose, and nobody gave me a second look in his baggy trousers and rolled sleeves. The next day he was off. We took a streetcar to the Haight-Ashbury district. We walked around, gawking at the hippies smoking pot on the sidewalk, painting each other’s midsection, selling handicrafts and enjoying a brisk day with warm sun and a chilly ocean breeze. I took a few photos. And then, quite suddenly, I saw a young man with two small children and a woebegone expression on his handsome face. Behind him was a wondrous store window. In seconds I composed and exposed. The image remains one of the strangest and most haunting photos I have ever made. Who was that man? What became of him and his children? My friend Robert, he died at age sixty of a heart attack. © 2018 Marvin J. Wolf

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

FROM Marvin J. Wolf

On this page are true stories, magazine articles, excerpts from books and unpublished works, short fiction, and photographs, each offering a glimpse of my life, work and times. Your comments welcome. © Marvin J. Wolf. All rights reserved. Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

|

|

Member, Military Writers of America

|

Website © 2016 Marvin J. Wolf. All rights reserved on website design, images and text. ꟾ Updated regularly.

Design by Andesign. |

Professional Reader, NetGalley

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed