My Pulitzer Luncheon

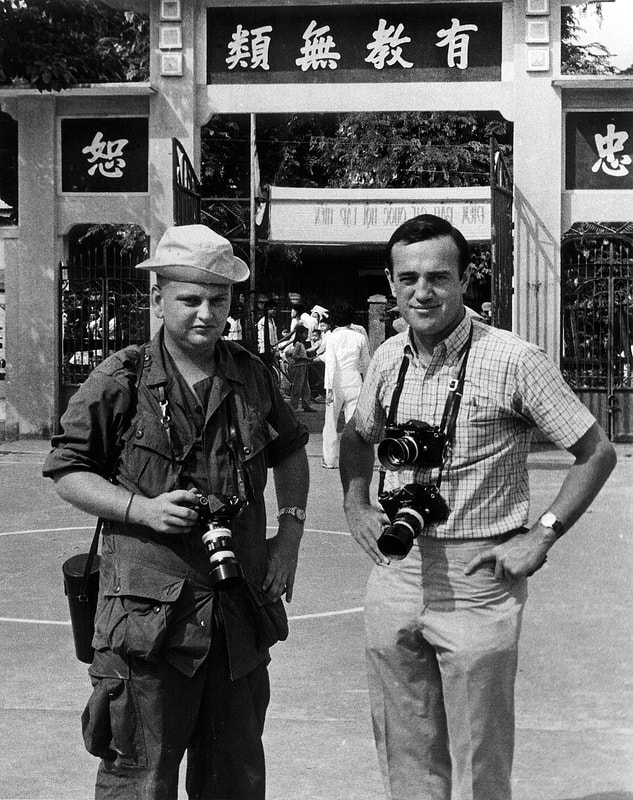

After weeks of bathing alfresco with tepid, often oily water splashed from my steel helmet, I was ready for a bath. Not that I felt more grungy than usual, not that I smelled any worse than my pals and peers in the First Air Cavalry Division public information office. But I was definitely ready for a bath. But first—lunch. Before that, however, I had an errand to run: the raison d’être for my journey from the monsoon-drenched Central Highlands to the fleshpots of steamy Saigon. I had to swing by the Associated Press bureau and drop off some film shot by one of their stringers. And, even more importantly, find a moment to talk with the bureau chief and suggest that it would be a really good idea if tomorrow he put a reporter on the flight to An Khe, where Major Chuck Siler, my boss, would make sure he got a helluva story. Can’t say what, exactly, I’d tell him, but trust me, it will be worth your while. This was the truth, and the news guys would know that military security being what it was I could not have simply telephoned over the radiophone circuit that linked our remote base camp to civilization. They also knew that my boss never lied to them, never sent them on a wild goose chase. And then lunch. Wherever I went, I knew the maître d’hôtel would take one look and exile me to a corner near the kitchen. But he wouldn’t turn away anyone who flashed genuine US greenbacks. Aside from the Military Payment Certificates in my wallet, I had a hundred bucks, wrapped in layers of plastic, in the left leg pocket of my fatigues. Most of that was intended for an antique chest in a shop on Boulevard Nguyen Huè, but five greenbacks would get me a seat in any Saigon restaurant; five more would bring anything on the menu. And I was ready. For months, all that had passed my lips were field rations, canned concoctions crammed with calories but nearly devoid of taste or texture. Turkey loaf was probably the best. C-ration spaghetti and meatballs approached passable when warmed, as did the canned tuna and noodles. But even when my olive-drab can held cold, congealed, grease-riddled ham and lima beans, I ate it. Humping those mountains with the grunts, hunting a story and pictures, burns calories. Very few combat soldiers are foodies enough to go hungry. But now I was primed for some real food, and all the way in from Tan Son Nhut Airport, bumping down potholed, overstuffed streets in the basket seat of a motorized cyclo, or pedicab, nothing between me and the traffic but my own thick skin, I thought about lunch. Maybe I’d cab it over to Cholon, to The Eskimo, with its blue and white tiled walls and its incomparable Cantonese cuisine. A spicy soup of shark’s fin, perhaps, with crisp pork-and-noodle spring rolls to be dipped in spicy nûc màum, followed by black mushrooms, bok choy and spinach greens sautéed in oyster sauce. Then prawns in a sizzling chili sauce. Maybe a smoked duckling as well. Fried rice, of course, and some side dishes. Lots of sides. At the bureau, I handed the plastic film bag to Bureau Chief Horst Faas and he hollered up the kid who worked in the darkroom souping film and making fast prints to send over the wire. The boy’s name was Huynh Cong Ut, but they called him Nick, a thin, undersized youth of about sixteen from a Mekong village. His older brother had been killed in action while shooting AP news photos, but Nick couldn’t wait for the day when he could leave the darkroom and be turned loose with a camera. For now, he seemed happy enough with a steady job working in an air-conditioned cubicle. “Let’s get lunch!” boomed Horst in his thick German accent. His English was sometimes hard to fathom, but his photos had earned him a Pulitzer Prize the previous year, 1965. “I’m in,” said Peter Arnett, the cocky New Zealander who earlier that year had won the Pulitzer for reporting. “I’ll come,” said Malcolm Browne, the bureau’s 1964 Pulitzer-winning reporter. “Me too,” said John Nance, who didn’t have a Pulitzer but was nevertheless a wonderful reporter with a fine flair for subtle detail and comedic irony. “Coming, young sergeant?” asked Peter in his clipped twang. “Good idea,” I echoed, trying not to sound too eager. Maybe these hotshots, all on expense accounts, would pick up my tab, too. “The Eskimo?” A chorus of nays overwhelmed my suggestion. It was too far for lunch. The food wasn’t what it used to be. Too many GIs had discovered the place. They’d had Chinese yesterday. “I’m ready for good French,” offered Malcolm in his quiet way. “Le Royale,” boomed Horst, and everyone nodded. Everyone but me. I was merely trying to launch a career in journalism while posing as an Army public information specialist. “What about Nick?” I asked. “He brings his lunch,” said Horst. It was past two by the time we had ambled a few blocks from the bureau, stepping over gutters mounded with fermenting garbage, tiptoeing to avoid sleepers stretched out along the shady stretches of steamy sidewalk for their afternoon siestas. Le Royale was a small hotel, but its restaurant was shuttered, the steel security gate bolted from the inside. My guts rumbled with hunger. “Got to be some place open around here,” I offered. “Hell with that!” growled Faas, pounding on the sturdy door with a ham-sized fist. He hammered and shouted until we heard the sound of a sliding bolt on the other side of the door. Finally, the portal was flung open and we were confronted by a burly old Frenchman in a cotton nightshirt, sleepy and ill-tempered—until he recognized his callers. “Bonjour!” he cried. “Welcome!” This was Jean Ottavij, a Corsican who had lived in Saigon for decades. In minutes he had shaken his slumbering Vietnamese sauciér awake, donned an apron and a tall white cap, and was slamming pots and pans around a huge kitchen stove. “Monsieur Faas, Monsieur Browne, Monsieur Arnett, it is the wonderful to zee you!” he bellowed through the open kitchen door. “And Monsieur Nance, and monsieur le sergeant, it is good to meet you, too! I will cook for you my very self!” There was no menu. In minutes the bouillabaisse appeared, a steaming tureen overflowing with firm prawns, chunks of tender lobster, slices of succulent abalone, shreds of crab legs the color of the setting sun, some tiny, crunchy, sardine-like creatures, long, faintly purple tendrils of baby octopus, chewy white rings of squid, tiny whole clams, fragrant leaves of celery, spinach and cilantro, hunks of potato— and all swimming in a broth that hinted at garlic, murmured onion and leek, whispered coriander and shouted tomato. Crusty baguettes of fresh bread and mounds of freshly-churned butter materialized. In what seemed like moments, it all vanished through our busy jaws. As if by magic, a fine Bordeaux appeared, and we uncorked sweating bottles of Vichy water and Biere Larue, Vietnam’s ubiquitous Tiger Beer. Next came an enormous platter on which rode an entire carp. Head and tail were attached but between them, the top skin was removed. The firm white flesh was covered with a sauce of small, tart, red berries and crunchy slivers of almond treading water on a thick brown sea that suggested apricot to my long-deprived palate. As the fish vanished, the ducks arrived, a brace graced with a caramelized sauce and slices of fresh oranges. Then our beaming host and his cook hefted onto our groaning table a behemoth platter of wafer-thin sirloin. Water buffalo, probably, but drenched in a savory condiment of red wine and tiny champignon and garnished with leaves of cilantro, so tender that it refused to be chewed and slid unaided down our gullets. Hardly had the plate made its rounds when its twin appeared. Then still another platter, this one with fried rounds of crispy potatoes heaped amidst little cubes of fresh tomatoes and decorated with fresh parsley and streaks of darkly pungent mustard. By the time the potatoes arrived, I was no longer hungry. But I had a soldier’s pride and didn’t fancy leaving the others to pull my oar, so I loosened my belt, put on my game face, and hunkered down into a posture conducive to serious chewing. The others indulged themselves heartily, some spearing food directly from the common dish, others first shoveling it onto their blue-and-white, octagonal plate. Except for the monotonous incantation of slavering jaws, the table fell silent. Then someone, probably Horst, sighed and observed that I could use a bath. “Apologies all around,” I mumbled. “Soon as I find a hotel room.” “Rick Merron is in the field, use his room at the Caravelle,” offered Peter. “Or try Tuohy’s, he’s in Japan for a few days.” “Much obliged,” I said, as the salad came, a glorious assembly of leaves of romaine, radicchio, escarole, and endive, quartered tomatoes, translucent wafers of cucumber and carrot, thin circles of purple onion, and all drenched in a subtle red wine vinaigrette. M. Ottavij, the elderly chef, took off his apron and toque, and clad only in the now sweat-stained nightshirt, joined us at the table. As we ate, ribald jokes, mostly in French but with asides in German, circled the table. I laughed with the others, hoping that later, maybe, someone would catch me up on what was said. And slowly, as I realized where I was and what I was doing, I entered a state of prolonged awe. I had been out in the field with journalists, plenty of them, since arriving in Vietnam six months earlier. I had shared a beer with a couple or three of these guys, but I had never, ever, simply hung out. And what a group this was, what an amazing fund of experience and accomplishment they represented to a kid who only a year earlier had belatedly decided that he wanted a career in journalism. The stories and anecdotes and jokes poured out, the food and drink disappeared, and finally, someone noticed that it was nearly five o’clock, and there was much work yet to be done at the bureau. “Then you must say adieu for now,” said our host. He shuffled off to the kitchen and returned with a bottle of Courvoisier, a tray with shot glasses, and a long sheet of paper—our bill. We filled our shot glasses. “Prosit,” announced Horst, and we upended our glasses. “I think I left my wallet back at the office,” said Malcolm, searching his pockets. “I’ve got maybe four hundred pee,” announced John. At the widely ignored official exchange rate, that was roughly a dollar’s worth of piasters. Embarrassed, Horst mumbled something about the Bank of India—the Indian or Pakistani-owned tailor shops which did a healthy trade in black market currency conversion. “I brought no cash at all,” sighed Peter. An uneasy silence settled over the room. I felt like a leper at a tanning salon. I reached for the bill, a long list of French scribbling with its numbers written in the European style. With the standard fifteen percent service charge, it came to a little over 18,000 piasters. “I’ve got it,” I said, opening my wallet. “No Army funny money,” warned Peter in a low voice. “Piasters or green.” I put away my wallet, dug out my plastic bag, and extracted three twenties. More than a week’s salary for a sergeant, including combat pay. I handed it over. “I have only piasters,” said the old Frenchman. Under the table, Horst stepped on my insole, hard. “We would be honored if you would accept the rest as a small token of our gratitude for a superb meal,” said somebody through my mouth, and our host inclined his head with all the magnanimous grandeur of a duke. “Only if you will accept another cognac before the departure,” he said, and the bottle went round again. On the sidewalk, Peter clapped my shoulder. “We’ll pay you back at the office,” he said. But long before we got there, I knew I wouldn’t take their money. For many months these men had treated me with kindness and generosity, and except for Major Siler, there were none that I admired more. And when would I get another chance to buy lunch for three Pulitzer Prize winners? I slept that night in the hotel room bed of the absent Bill Tuohy, a Los Angeles Times reporter, and damned if he didn’t win a Pulitzer a couple of years later. Horst won his second Pulitzer in 1972. And then the next year, the kid from the darkroom, young Nick Ut, won the Pulitzer for what remains arguably the most memorable photo of the entire war: a naked little girl fleeing a napalmed village. I should have brought Nick a doggie bag. © June 2023 Marvin J. Wolf. All rights reserved. #Pulitzer #Vietnam #VietnamStories #foodies #photojournalists #PeterArnett #BillTuohy #NickUt #MalcolmBrowne #JohnNance #napalm

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

FROM Marvin J. Wolf

On this page are true stories, magazine articles, excerpts from books and unpublished works, short fiction, and photographs, each offering a glimpse of my life, work and times. Your comments welcome. © Marvin J. Wolf. All rights reserved. Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

|

|

Member, Military Writers of America

|

Website © 2016 Marvin J. Wolf. All rights reserved on website design, images and text. ꟾ Updated regularly.

Design by Andesign. |

Professional Reader, NetGalley

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed