|

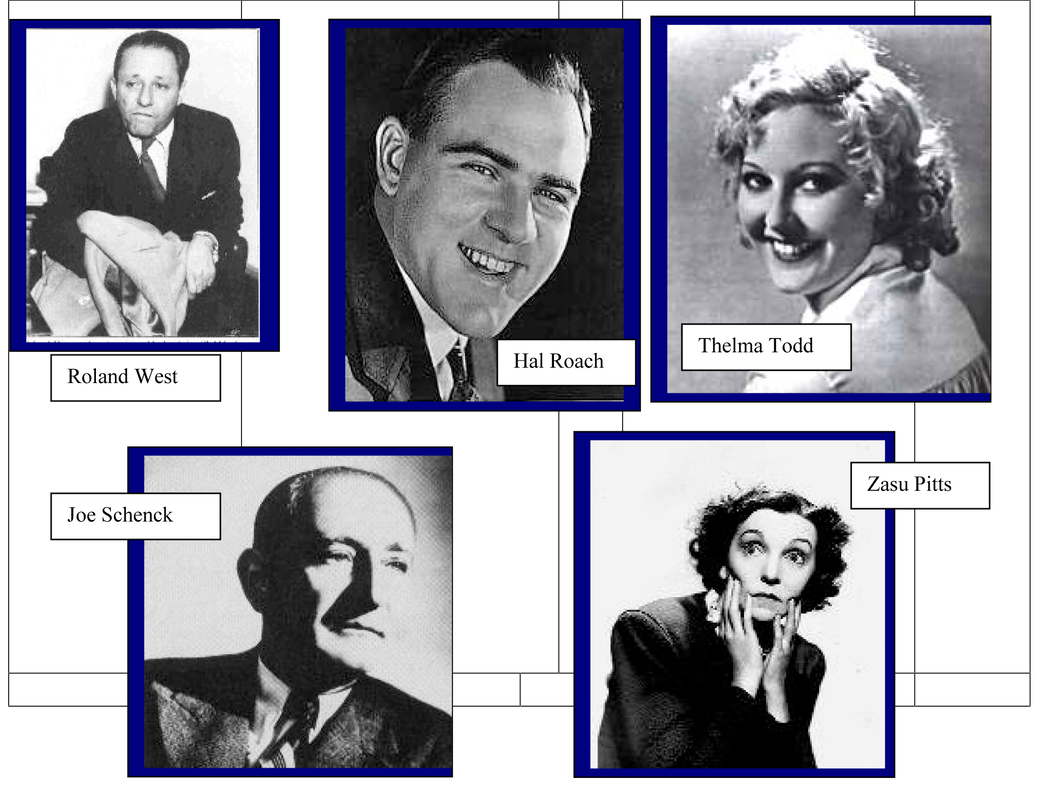

From Los Angeles Magazine December 1987 "Dark Strangers, suicide, a jealous boyfriend, Mob connections — all have been fingered at one time or another for Thelma Todd's death." May Whitehead pulled up alongside the cliff-side wall high on Posetano Road above Will Rogers Beach. She walked to the garage carrying several bundles in her arms. As always, the massive doors were closed but not locked. Whitehead juggled the packages to free one hand, then slid back the right-hand door. Inside were the shiny grille and headlamps of her boss' chocolate-colored 1933 Lincoln Phaeton. It was 10:30 on the cold but sunny Monday morning of December 16, 1935. Whitehead, attractive, erudite and black, was Thelma Todd's personal maid and confidante. She was responsible for getting the curvy blond comedienne to work on time at the Hal Roach Studio in Culver City. She would pull Todd's Lincoln out of the garage, leave her own car in its place, then drive the steep, meandering lanes to a white stucco building at the bottom of the hill on what is now Pacific Coast Highway. The rambling, vaguely Mediterranean three-story building housed Thelma Todd's Sidewalk Cafe, a chic, pricey and popular restaurant operated by Todd's partner and lover, film director Roland West. On this morning Whitehead approached the Lincoln from the passenger side. With a start she saw Todd slumped behind the wheel, her eyes closed, her head inclined toward the car's open door. She was wearing a full-length mink coat over a metallic blue sequined evening gown and matching cape, blue silk slippers and about $20,000 worth of jewelry, including a square-cut diamond ring, a diamond-studded wristwatch, pin and brooch and two diamond hair clasps. She wore, in fact, exactly the same outfit Whitehead had dressed her in to attend a celebrity-studded dinner party at the Sunset Strip's trendy Trocadero nightclub the previous Saturday evening. "I went around to the left side of the car, the driver's side," Whitehead later told a coroner's jury, "and I thought I could awaken her, that she was asleep." But Thelma Todd, "the Ice Cream Blonde," "the Blond Venus," Hollywood's notorious party girl, was dead. Whitehead ran back to her car and drove to the cafe, where she got hold of Charles Smith, the septuagenarian café treasurer and veteran assistant film director who'd served Roland West for decades. West, 48, was a little shorter than Todd's five-foot-four, swarthy and sharp featured. He and Todd lived in modest second-floor apartments connected, for an outward show of propriety (West was still married to silent-film star Jewel Carmen), by sliding doors that could be locked from either side. Adjacent to the apartments was a private club, Joya's, and an oversize lobby with couches where "overtired" guests sometimes napped. Smith buzzed West, who was upstairs and apparently still asleep, on the intercom. West appeared in minutes, ashen faced and carelessly dressed, and leaped into Whitehead's car. In her excitement, on the way back to the garage Whitehead missed a turnoff and had to stop and turn the car around in the narrow lane. At the garage, West raced inside and put a hand to Todd's face. He pulled his hand back, there were a few drops of blood, which he wiped on his handkerchief. West told Whitehead to fetch Rudolph Schafer, the cafe manager and his brother-in-law. Schafer lived in Castillo del Mar, an enormous hillside villa owned by West's estranged wife, which overlooked West and Todd's place. Schafer, who had also been asleep, got to the garage about 11:15. He touched Todd's cold cheek. The police must be called, he decided, and West agreed. Electing not to use the phones at the Sidewalk Café or those at Castillo del Mar, Schafer took West's Hupmobile, parked as usual in the stall next to Todd's Lincoln, and drove several miles to a Santa Monica print shop, where he called the LAPD's West Los Angeles station on the proprietor's private phone. At the death scene police noted no signs of violence. There were 2.5 gallons of gas left in the Lincoln's tank; the ignition was on, but the battery was completely discharged. On the seat was Todd's small white party purse. Inside was a key to her apartment's outside door. Thus began one of the strangest chapters in the history of Los Angeles crime. Immediately, the 29-year-old actress' death made page-one headlines across the country. As the investigation wore on, the local papers were filled for months with speculation, rumor and charges-most of them unfounded and inaccurate — that soon made the case one of Hollywood's most sensational unsolved deaths. Over the years, scores of articles and books have been written hypothesizing what really happened to Thelma Todd that night in 1935. "Dark strangers," suicide, her jealous boyfriend, mob connections — all have been fingered at one time or another for her death. But despite more than five decades of speculation and hype, the final chapter of Thelma Todd's mysterious death has remained unwritten. Until now. What follows, for the first time, is the true story of what happened that night-and why Hollywood conspired to keep it a secret for half a century. Thelma Todd was born in Lawrence, Massachusetts, in 1906. Her father was an important local figure, a merchant and perennial alderman. At 15 Thelma went to work in a dime store, but when crowds of people, mostly young men, jammed the store merely to look at her natural beauty, the proprietor had to fire her. The Lawrence Elks club proclaimed her Miss Lawrence and sponsored her in a statewide competition in which she became Miss Massachusetts. For extra money during high school, she modeled clothing in a local theater, so impressing Napoleon DeMara, manager and principal performer for a community theatrical troupe, that he sent her picture to Jesse Lasky at Paramount. Lasky liked what he saw. Studio press agents would later describe her as a former schoolteacher, but despite being elected freshman-class spokesman, Thelma dropped out of Hood Normal, a teacher's college, after one year to attend Paramount's training school in Astoria, Long Island. She graduated with the class of 1926, which included such later notables as Buddy Rogers and Josephine Dunn. Todd's first film was God Gave Me 20 Cents. Paramount liked her way with fine clothes and her forceful, intelligent looks. She appeared in 13 silent films, easily making the transition to talkies in 1927. She had a vibrant, cultured speaking voice and strove to enhance it with voice lessons. By the late Twenties her private life was being radically shaped by her sudden affluence and Hollywood's fast, hedonistic society. In July 1932 she eloped with Pasquale ("Pat") De Cicco, an agent, to Prescott, Arizona. But she was already accustomed to the fast lane. She had affairs with actor Ronald Colman, band leader Abe Lyman and several other men before divorcing De Cicco in March 1934. Thelma acquired faster and faster cars. She drank freely. She was cited for speeding and for driving under the influence. And on January 23, 1933, she ran into a palm tree near Hollywood Boulevard and Nichols Canyon, suffering three broken ribs, a shattered collarbone and internal injuries. She contracted peritonitis and hovered on the brink of death, then rallied. When the Roach studio forbade her to drive, Thelma began taking Whitehead along to drive and hired Ernest Peters as her party chauffeur. Todd's career had taken a new turn when she met Roland West in 1930. The director changed her screen name to Alison Lloyd — "so that no taint of comedy would cling to her skirts" — and starred her as a jaded, manipulative, pleasure-seeking debutante opposite his good friend Chester Morris in Corsair. Though Todd would later appear in other dramas with such superstars as Humphrey Bogart, Randolph Scott and Gary Cooper, she went back to being Thelma Todd after producer Hat Roach half-seriously threatened to change her name to Susie Dinkleberry "so that no taint of drama would cling to her skirts." Roach knew that Depression-era audiences wanted to laugh, and nobody in skirts was funnier than Todd, who went on to star in such comedy classics as Horsefeathers and Monkey Business with the Marx Brothers. But Corsair was to be West's last film, and before it was finished he and Todd began their tempestuous affair. And though he strenuously denied a relationship with Todd, it was to last, off and on, for five years, until her death. From the beginning, the investigation generated controversy and conflicting reports. For weeks after Todd's death the city's lurid dailies ran stories recounting purported details of her last hours. The first mystery confronted by the police was why Todd had not slept in her apartment. Todd had been driven from the Trocadero and dropped off at the entrance to the café by her chauffeur at 4 a.m. Sunday morning. She had not taken the keys to the main ground-floor entrance or to the inside en-trance to her apartment, but she carried one to the outside entrance to her apartment. How is it, the coroner asked Roland West, that she didn't use it? West told the coroner that, not realizing Todd wasn't carrying her other keys, he'd bolted the outside door from the inside because of recent prowlers and death threats against Todd. He retired at 2:30 a.m. Sunday morning, but at about 3:30 a.m., he said, he was awakened by the whining of his bullterrier, White King. The dog would have barked if anyone except he or Todd were nearby, said West, so he assumed Todd had returned. Later, hearing an electric water pump, he concluded that Todd was using the bath. He awakened Sunday morning to find Todd gone. Judging by an impression left on a lobby divan, West said, he assumed she had slept there, rising early to depart, perhaps to visit her mother in Hollywood. Police eventually advanced the theory that Todd, finding herself locked out, had decided to sleep in her car and climbed the 271 steps cut into the steep cliff behind the café to the garage. It was an exceptionally cold and windy night, and she might have started the engine to keep warm. Since the autopsy revealed a blood-alcohol content of .13 percent-. .8 today is considered the legal threshold of intoxication-she might have dozed off before being overcome by the engine's fumes. But that theory immediately came under attack. Todd hated to walk, insisted West. She had a heart condition, he said, and her physician had forbidden strenuous exercise. Though the autopsy indicated no heart or other organ abnormalities, West claimed Todd was subject to frequent "fainting spells" because of her heart condition. Nobody publicly asked why Todd would have chosen to sit freezing in her open-topped phaeton when West's unlocked Hupmobile sedan was right next to it. The press seemed bent on discrediting the police investigation. Several papers dug up stories with remarkable testimony. of people who claimed to have seen or spoken with Todd well after the time of death fixed by the coroner: "anywhere from 5 or 6 o'clock on to 8 o'clock" on Sunday morning, December 15. Hearst's L.A. Examiner ran a page-wide headshot of autopsy surgeon A. F. Wagner over the headline "I do not believe she could have died earlier than 5 or 6 o'clock last Sunday after-noon." Totally inaccurate, it served to heighten the mysteries of Todd's last hours. Despite the inquest testimony of LAPD captain Bruce Clark, the first cop on the scene, that the bottoms of Todd's silk slippers were "scuffed up quite a bit" and "gave the appearance or indication she had walked quite some distance on cement," it was widely reported that her slippers showed no sign that she could have climbed the 271 hillside steps, the most direct route between the café and the garage. So much play was given this bit of disinformation, in fact, that the LAPD had a 120-pound woman, the same weight as Todd, climb the stone steps in similar slippers, to the delight of the press, who witnessed the test but all but ignored the results, which confirmed the inquest testimony. Some news accounts described a tooth knocked from Todd's mouth; others turned the few specks of blood found on Todd's lip into a fountain of gore. One police-beat reporter wrote about great bruises inside Todd's throat, suggesting they'd been made by a Coke bottle. There was in reality no broken tooth or any bruises, and the tiny bit of bloody froth on Todd's lip was consistent with postmortem changes in mucous membranes typical of carbon-monoxide poisoning — facts contained in the coroner's report but never publicized. There was one possible witness, night watchman Earl Carder, who by his own calculations walked past the death scene 15 times between midnight and dawn-an average of once every 24 minutes. But Carder, tall, burly and employed by West, said he neither saw nor heard anything unusual. As the investigation continued, rumors of foul play took on a new slant. Todd's hired driver, Ernest Peters, had testified to dropping Todd off at the Sidewalk Café just before 4 o'clock Sunday morning. Oddly, for the first time in the three years Peters worked for her, Todd had declined his offer to escort her to the outside door of her apartment. Peters testified that Todd said nothing at all on the ride home; nonetheless, reporters were soon quoting him as saying that after leaving the night-were soon quoting him as saying that after leaving the nightclub, Todd insisted he drive faster because she feared being killed or kidnapped by "gangsters." Then two men who worked at a Christmas-tree lot in Holly-wood came forward to report selling Todd and a "dark stranger" a tree at around midnight Sunday, adding, days later, that two burly gunmen in a long black car subsequently warned them against telling police they'd seen Todd. Soon anonymous officials were leaking stories about a supposed Mafia connection. It was alleged that Lucky Luciano's mob, attracted by the Sidewalk Cafe's semi-remote location and wealthy clientele, had sought to open an illegal casino on the third floor and that when Todd opposed it she was murdered. The press also made much ado about Todd's Trocadero attendance in the company of such luminaries as Sid Grauman, British director Stanley Lupino, his daughter, Ida, and starlet Margaret Lindsay, who arrived on the arm of Pat De Cicco, whom Todd had divorced nearly two years earlier. De Cicco was attending another party there, but the dailies made much of the couple's inevitable meeting, insinuating that he sought to embarrass his ex-wife by bringing along another woman. It was all irrelevant but titillating. The press, however, weren't the only ones who had doubts about the Todd case. Grand jurors were not persuaded by the collectively incredible testimony from the parade of celebrities who seemed to go out of their way to contradict each other. West, for instance, insisted that if Todd had attempted to start her car, it would have awakened Smith, who lived in rooms above the garage. He insisted that the Lincoln's 12-cylinder engine was loud and pointed out that there was a large hole in the garage's plaster ceiling. The assertion got a lot of newspaper ink. In a reenactment, the hole proved smallish and far from the upstairs bedroom. Police listening for engine noise heard nothing. Jewel Carmen, West's wife, testified to seeing Todd, dressed quite differently from the way her body was found, driving her car with a dark, mysterious man beside her on Sunday evening. Carmen adroitly avoided cross-examination by collapsing on the witness stand, though she later was sufficiently recovered to give Louella Parsons an "exclusive" interview confirming West's contention that he and Todd were merely friends. To further confound the matter, despite Whitehead's testimony that Todd detested using telephones and always go someone else to make her calls, two witnesses — a middle-aged male liquor-store owner and a widowed druggist-swore that Todd had used a pay phone in their respective establishment Sunday afternoon and evening. Even more astounding, Mr. Wallace Ford, wife of the noted actor, insisted Todd had telephoned her Sunday afternoon. to confirm an invitation to the Fords' cocktail party. "Several witnesses have not told all they know," said one juror. It wasn't long before some began to suspect a cover-up. "Some of those who appear most mute, most dumb, apparent are deliberately concealing facts," noted grand-jury foreman George Rochester. "Potent Hollywood interests have tempted to block the probe [into Todd's death I from the beginning," he added, warning witnesses about perjury. Likewise, prosecutors smelled something rotten. "falsehoods have been told by certain witnesses inside the grand-jury room," complained deputy DA George Johnson. "Someone covering up something. Someone, we think, knows how Thelma Todd died ... none of the apparent facts smooth out." "Has pressure from some influential source been brought I hear in an attempt to halt this investigation?" a reporter asked Rochester. "We are not stopping," he replied. But the witnesses stuck to their stories. In the end, the grand jury did stop. Todd's death was left an accident. Case closed. But not solved. As it turns out, some in the police department knew very well who killed Thelma Todd, and how as well as why. They kept their silence but closed the file only when the killer died in 1951. Still, the real story could not be told. A handful of powerful Hollywood insiders with long memories and wide connections maintained a conspiracy silence. Even after the architect of the conspiracy died in 1961 associates continued to suppress the story. Over the years, whenever a film studio expressed an interest in the mystery of Todd's death, someone always intervened, and the idea was quietly dropped. To comprehend exactly what transpired, it is necessary to understand a little about the times and the principals involved. The Todd affair was particularly sensitive to L.A. film, business and civic leaders of the day because on the very day her body was found, Warner Bros. director Busby Berkeley went on trial for three counts of second-degree murder for his alcohol-related head-on collision with another car on Pacific Coast Highway, not far from Todd's café. If there was one thing the L.A. Establishment did not want, it was yet another showboat murder trial involving alcohol and a noted director. Now an almost forgotten figure, Roland West was at the time one of the most innovative directors in Hollywood, pioneering techniques that now seem strangely modern. His film noir scenarios were all variations on a single theme: the workings of the criminal mind. West's amoral protagonists typically masquerade behind respectable public images, as in The Bat and its talkie sequel, The Bat Whispers. In Corsair, a college football hero quits a brokerage firm after realizing he's preying on widows and orphans, only to become a thuggish, manipulative rum runner. By guile and brute violence, most of West's protagonists manage to evade punishment for their crimes. It was while performing in the play The Criminal, in which he appeared for years on the vast Loews theater circuit, that West met Joe Schenck, then Loew's booking manager. West soon turned to producing, and in 1912 he directed his first film, Lost Souls, produced by Schenck. Schenck was born in Rybinsk, Russia, on the Volga, Christmas Day, 1877, and came to New York at age 10. He and younger brother Nicholas earned $4.50 a week as factory laborers. They soon became drugstore delivery boys in New York's Chinatown. After several years of hustling, Joe had saved enough money to start a New Jersey amusement park, with Nick as a partner. Schenck displayed a genius for show business. He parlayed the Jersey property into a larger one in the Bronx, then sold that to Marcus Loew and, along with brother Nick, went to work for him. Schenck left Loew's in 1912 to launch a movie business with Roland West. In 1917 he stole Fatty Arbuckle away from Keystone with a salary increase, an independent production deal and the keys to a new Rolls. Like many a Schenck deal to come, it was all done on a handshake. In 1917 he took his company to California. By 1921 Schenck's man Arbuckle was the nation's second-biggest box-office draw. But over the Labor Day weekend Arbuckle touched off the film industry's most infamous scandal. Arbuckle was charged with the rape and murder of actress Virginia Rappe during a drunken orgy he hosted at a San Francisco hotel. The day Fatty was arrested, Schenck pulled ..is latest film from distribution. Within days, cities across the country passed ordinances barring Arbuckle's films from theaters. With their friend, former postmaster general Will Hays, the Schencks created an industry watchdog agency and helped promulgate the infamous morals clause. The Arbuckle scandal proved that Hollywood needed a place to play where moviegoers' disapproving eyes couldn't see them. That led Joe Schenck and a number of partners, including local vice lords and the very respectable Jacob Paley (father of William S. Paley, founder and chairman of CBS), to open an exclusive resort, complete with casinos, racetrack, hotel and fine restaurants, at Agua Caliente, near Tijuana. As the major investor, Schenck was chairman of the board. Schenck became chairman of United Artists in 1924. In 1933 he left to found 20th Century Productions along with Louis B. Mayer's son-in-law, William Goetz, and Darryl F. Zanuck. Initial capital of $750,000 was put up by Mayer and by Nick Schenck, who was by then running Loew's. In 1935, 20th Century bought Fox, which was in bankruptcy but con-trolled a huge chain of theaters. Schenck soon became one of California's wealthiest men, with vast real-estate holdings in Arizona and California. For a time he owned, with Jacob Paley, Del Mar Race Track and a Lake Arrowhead resort. He controlled the Federal Trust and Savings Bank and was a major stockholder and director of the Bank of Italy, now the Bank of America. He became great friends with William Randolph Hearst. At the time of Todd's death, he was already one of the most powerful men in the Industry. His brother was the head of Loew's and MGM and therefore the boss of Hal Roach, the man who had made Todd a star. As writers, we first became familiar with the Todd case while researching it for a recent book, Fallen Angels, which chronicles 39 true stories of Los Angeles crime and mystery. But since we had to rely on mostly secondary sources in researching all the chapters, the death remained an enigma. For years we'd heard rumors about the case, and Katherine Mader, who grew up in Pacific Palisades near the scene of Todd's demise, insisted we could solve this crime. There had to be somebody still alive from the era who knew what had happened. In the spring of 1987, after finishing the book, we had, for the first time in years, time on our hands. We began prodding a screenwriter friend who, between family connections and writing projects, had become something of an authority on old Hollywood. He admitted to having heard whispers about Todd's killer, but he refused to go any further, saying he couldn't betray confidences. Instead he referred us to a number of low-profile industry insiders. For the most part, however, they either ducked our questions or referred us cryptically to still other people, most of whom turned out to be long deceased. Even so, the one name that kept coming up again and again was Hal Roach. We were somewhat surprised to find that, at 90, the legendary comedy producer was still very much alive. However, when we finally got hold of him on the phone he was alternately accommodating and evasive: First he was ill with a virus; then a few weeks later, he was too busy; then he was going out of town. Finally, though, Roach agreed to meet us at his home and talk about Thelma Todd, whom he remembered fondly. When we were at last seated in his den, surrounded by an impossible number of film-celebrity photographs and other mementos documenting a career that began in 1912, Roach skipped the preamble and went right to the point. On December 17, 1935, the day after Todd's body was found, three Los Angeles County sheriff's detectives came to Roach's studio office. The deputies told Roach that Roland West, under intense questioning, had confessed to killing Thelma Todd. "West was very possessive, very controlling," said Roach, the last survivor of the affair. "He told Thelma she was to be back by 2 a.m. She said she'd come and go as she pleased. They had a little argument about it, and then Thelma left for the party. When Sid Grauman called West, about 2:30, to tell him Thelma was leaving, West went into her apartment and locked her out. He was going to teach her a lesson. "Apparently when Todd returned at almost 4 a.m., she declined her chauffeur's offer to walk her upstairs because she knew there would be a scene with West. When she found the door locked, she shouted at him, and they had another argument through the door. West told her he didn't want her going to so many parties. Todd, still a bit drunk, screamed that she'd go to any party she pleased. She was invited to one later that day, at Mrs. Wallace Ford's, and she said she'd just go to that party now." According to Roach, she climbed the steps to the garage. West followed. When he arrived she was already in her car. She started the engine, and he ran around and locked the garage door. "He wasn't thinking about carbon monoxide, just about teaching her a lesson about who was the boss. So he left and went back to bed," says Roach. After daylight West returned to the garage to find Todd's body. "He didn't know what to do," says Roach. "So he did nothing. He closed the door — but didn't lock it — and went back to the cafe. All that day, when people called for Thelma, he said he didn't know where she was. If he really hadn't known where she was, he would have been calling all over trying to find her. That's the kind of man he was." We listened in barely suppressed excitement. Besides naming the killer, Roach was admitting he had played a role in a cover-up. The sheriff's detectives had called on Roach, it turned out, because they were sent theme to seek his opinion on what they ought to do about West's confession. "I told them I thought they should forget about it," says Roach. "He wouldn't have gone to jail anyway, because he'd have the best lawyers, he'd deny everything in court, and there were no witnesses. So why cause him all that trouble?" We left Roach's house in a state of wonderment. Out on the street, blinking in the brilliant sunshine of midday Bel Air, we compared notes. A trio of deputy sheriffs had visited Roach. Though that was illuminating, it raised more questions than it answered. Who sent them? Whom did they report to after leaving Roach? And would Hal Roach, in 1935 at the height of his influence, have had the clout to stop a police investigation? It was all very unsettling. The first issue to consider was why Roach should have protected the man who killed his $3,000-a-week star. One reason, of course, was that implicating West would have meant exposing Todd's adulterous affair, and that could have meant a scandal like the Fatty Arbuckle affair some years earlier, surely at the price of heavy box-office losses for his studio. The deputies left, and the case against West never surfaced. But, as we soon learned, Roach was hardly such a powerful figure that three deputies would simply take his advice and quash a wrongful death investigation. It was also difficult to believe that the deputies who visited Roach could have many any decision concerning a homicide case without consulting someone in higher authority. So, who sent the detectives to Roach in the first place? Whoever dispatched the deputies to talk to Roach had to have worked for the sheriff. A few days spent prowling dusty stacks and uncatalogued archives in the USC Library convinced us that Eugene Biscailuz, who in 1932 had resigned from the California Highway Patrol to win election as sheriff, was well acquainted with former highway commissioner Joe Schenck, He was a frequent visitor to Agua Caliente and was often photographed visiting film locations and studio sets with Darryl F. Zanuck, Schenck's partner, and with Mayer, whom Biscailuz made an "honorary deputy.' Biscailuz also knew Todd's best friend, Zasu Pitts, a heavy contributor to his election campaign and in whose private car the he had installed a police siren. And Biscailuz knew Roland West as a 32nd-degree Mason and lodge brother, at a time when such associations meant a lot. Though it's rare, the Sheriff's Department can investigations of crimes committed within its boundaries. Biscailuz chose to do so in 1935. He was also very good friends with deputy DA U. U. Blaylock, the man who helped prepare and present the Todd case to the grand jury, which was to return no indictment. As sheriff and as a deeply rooted Angeleno, Biscailuz had an institutional interest in the film industry's financial health: The movies were the nation's fifth largest industry and L.A. County's most visible. As for the LAPD, in 1935 Mayor Frank Shaw ruled Los Angeles like a private fiefdom. Police corruption was so pervasive that when in 1937 Shaw was recalled from office, dozens of senior officers fled to avoid prosecution. In. 1935, anyone with money to spread around could have easily gotten to the LAPD. Chief of Detectives Thad Brown, who knew West had killed Todd, was told to back off "because there was no evidence." Obviously the police had conspired to suppress West's confession, a fact known by only a handful of senior cops. (The Todd file was said to be among dozens of suppressed records seized by an LAPD flying squad from Thad Brown's garage hours after his death. The files have never been made public. With the Fatty Arbuckle imbroglio still a vivid memory, avoiding yet another movie scandal became Joe Schenck's chief concern. But he had other reasons as well — reasons that hit a little closer to home. In 1941 Schenck was convicted three counts of tax evasion and one of perjury. Schenck's tax-evasion charges included unreported income between 1935 and 1937, preposterous "business deductions" and a stock-sale fraud. In 1935 a new Mexican dictator issued an edict "outlawing" gambling. Translated, this meant that he expected a bigger cut. Schenck, who controlled Agua Caliente's lucrative gaming, would eventually spread enough money around Mexico City and Baja California to come to terms with the new government, but in the meantime he saw an opportunity to recoup his investment. As Roland West later testified, Schenck sold him $410,000 in Agua Caliente stock for $50,000. Schenck then took a tax loss of $360,000, though he never actually transferred the shares and continued to vote them for years through hidden proxies. To make it easy for West, Schenck had his company, Fox, loan West the price of the stock. West gave Schenck a check; Schenck then secretly reimbursed West in cash, money which he in turn used to pay off the Fox loan. West's first $5,000 installment was paid in July 1935. The balance was to be paid in $5,000 installments. According to uncontroverted testimony at Schenck's trial, West paid the second installment and was secretly reimbursed on December 17, 1935, the day after Todd's body was found West's garage. It was the same day the three deputies visited Roach, a day when West and Schenck had much to talk about Though Schenck's concern for the Industry was a compelling factor, his eagerness to cover up the potential scandal had a much more immediate cause: keeping his lifelong friend away from any temptation to trade information on Schenck's tax fraud in return for a reduced sentence. (Schenck himself eventually got a reduced sentence of $432,050 in fines and back taxes and served four months in prison.) Nobody was ever indicted for Thelma Todd's death. Any attempt to penetrate the veil of secrecy surrounding the affair was met with stony silence for as long as Joe Schenck and his associates lived. To this day, Hal Roach continues to deny knowing of any connect between Schenck and West. Released from prison in 1942, Schenck began rebuilding image by leading innumerable Industry and Jewish charity drives. While FDR lived, Schenck's particular favorite charity was polio. He is credited with inventing the March of Dimes concept and with getting collection boxes put in nearly all US movie theaters. Sheriff Biscailuz won the contested reelection campaign in 1936 — and went on being reelected until he retired in 1958. After 1935, however, he distanced himself from the studio moguls. From then on, he limited his Industry exposure to public events and photo opportunities involving charitable causes, posing for photos with an endless stream of film stars, but always within the security of his own office. On his Saint John's Hospital deathbed in Santa Monica in 1951, a guilt-ridden West confessed his role in Todd's death to a close friend, actor Chester Morris. Morris, who committed suicide in 1972, repeated West's confession to director Gordon, who recently confirmed it for the writers. Last year, after speaking about Fallen Angels at a Biltmore Hotel literary event, we were introduced to Don Gallery, adoptive son of film comedienne Zasu Pitts. After we spoke to Roach, we tracked Gallery to his home on Catalina Island, where he confirmed that his mother, Thelma Todd's best friend, had once confided an almost identical version of her death. Joe Schenck died on October 2, 1961, in Beverly Hills. Pallbearers included Irving Berlin, Sam Goldwyn and Jack Warner. In his eulogy, Association of Motion Picture Producers president Y. Frank Freeman told the assembled. Hollywood mourners, "Joe Schenck never waited for a man who needed help to come to him. He went to that man for that purpose." © 1987 Marvin J. Wolf and Katherine Mader

16 Comments

hmj

9/14/2020 01:58:57 pm

Thank you for posting this. I have read a lot about the death of Thelma Todd lately. There is a lot of false information around the mob being involved. I was inclined to believe it was an accident, she had taken a small purse to the Lupino party and didn't want to take her full set of keys. She didn't want to wake up West, who had been working at the cafe all day, so she decided to have a nap in her car and wait until the cafe opened. It was also a very cold and windy evening. The parts that don't make sense are, why wouldn't she knock and bang on the door to wake West up, he even admitted nothing could keep Thelma out of a place if she wanted in. Why did she refuse her driver's offer to walk her up. If there was a chance she was locked out he could have taken her somewhere. She obviously went into that garage of her own free will, she wasn't beat up, rendered unconscious. I can see them having an argument and Thelma going up to the car. If West locked her in the garage I would imagine her banging on the door and making a fuss until she was overcome by the carbon monoxide or went back to turn the engine of the car off and passed out in the process.

Reply

Paul Silver

3/24/2021 12:06:35 pm

The thing I don't understand is they found the key in the ignition, but the engine off, and gas still in the tank. Who turned off the engine?

Reply

Lynnedee

7/29/2021 10:18:48 am

The article said that the battery was dead, which was why there was still gas in the tank. 8/11/2022 02:35:12 pm

According to Hal Roach, Todd knew that she would likely have to wake West up, and there would be a shouting match. She didn't want her driver to hear that, because she feared he would try to protect her from West when he opened the door.

Reply

ADW

4/4/2021 10:57:29 am

The only person who knew the truth was Thelma Todd. I have read numerous books and theories of her death and like Marilyn Monroe, JFK and Dorothy Killgallen , the person or persons responsible for their deaths will remain a mystery.

Reply

4/4/2021 11:06:03 am

Hal Roach told me and my colleague Kathryn Mader, then a deputy L.A. County District Attorney, that two LAPD detectives had told told him that West had confessed to locking Todd in the garage. This was either after or before she had started the engine. It is possible, even likely, that Todd was unaware that the door was locked until it was too late. She was full of alcohol, tired, and might have dozed off after starting the engine. Or perhaps she was cold and started the motor to use the heater. Either way, according to Roach, who was central to the cover-up, the LAPD and the LA Sheriff were sure that West was responsible.

Reply

ADW

4/4/2021 02:00:11 pm

To have met with and interviewed Hal Roach had to be a great experience but I still have my reservations about who was guilty. Roland West had a stroke and nervous breakdown shortly before his deathbed confession and unless the police had a signed copy from 1935, it's heresay. If I had to choose a suspect then I would go with Lucky Luciano and his circle. Thelma was "seen" with him, he wanted the 3rd floor of her cafe and she said no (also heresay).Hollywood was well aware of mod infiltration at the time and what could happen to you, no matter who you were, so a police cover up would be no surprise. I know you didn't create a theory but relayed a story as told to you by Hal Roach. I'm anxious now to get a copy of your book "Fallen Angels". It sounds fascinating.

Reply

Jack Todd

12/19/2021 04:55:49 am

So what explains the two cracked ribs she endured?

Reply

Tasha

2/3/2022 07:35:14 am

I believe the cracked ribs were urban mith that over the decades have been presented as truth. The autopsy says nothing about broken ribs. Sometimes the truth is just as simple as this…her death death resulting from the locked garage door.

Reply

HMJ

2/3/2022 08:00:48 am

Same as the broken nose and that she was hanging around with Lucy Luciano. It was mentioned in a book by Andy Edmonds but there was no evidence to support this. 2/3/2022 09:16:37 am

You are correct. When I wrote this piece many years ago, I had a copy of the coroner's report, and I had also gone to the USC library which has the morgue of the long-deceased Herald. I found the multiple reports in this periodical and they were unfailingly different from facts presented in the coroner's report. Obviously, Hearst's minions had orders to muddy the waters and divert blame from West.

paul

5/8/2022 10:12:42 am

A fascinating but sad story, sometimes the truth is simple and not overly complicated.

Reply

Adw

7/12/2022 08:24:26 pm

I've read your other fodder and you are a self impressed, dogmatic hack. An interview with Hal Roach if it ever took place is of no value. You have solved nothing and you need to stop trying to be a an authority on subjects you are so ignorant about.

Reply

8/11/2022 02:42:24 pm

Thank you,

Reply

8/11/2022 12:03:02 pm

FOR WHAT IT'S WORTH, FRANK McHUGH TOLD ME THAT THE L.A. POLICE CLOSED THE BOOKS ON THE THELMA TODD CASE ONLY UPON THE DEMISE OF ROLAND WEST IN THE FIFTIES. McHUGH APPEARED IN WEST'S LAST MOTION PICTURE, "CORSAIR" (U.A.; 1931), IN WHICH TODD HAD THE FEMALE LEAD AS "ALISON LOYD".

Reply

Kevin

10/15/2022 06:38:40 pm

Hi

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

FROM Marvin J. Wolf

On this page are true stories, magazine articles, excerpts from books and unpublished works, short fiction, and photographs, each offering a glimpse of my life, work and times. Your comments welcome. © Marvin J. Wolf. All rights reserved. Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

|

|

Member, Military Writers of America

|

Website © 2016 Marvin J. Wolf. All rights reserved on website design, images and text. ꟾ Updated regularly.

Design by Andesign. |

Professional Reader, NetGalley

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed