|

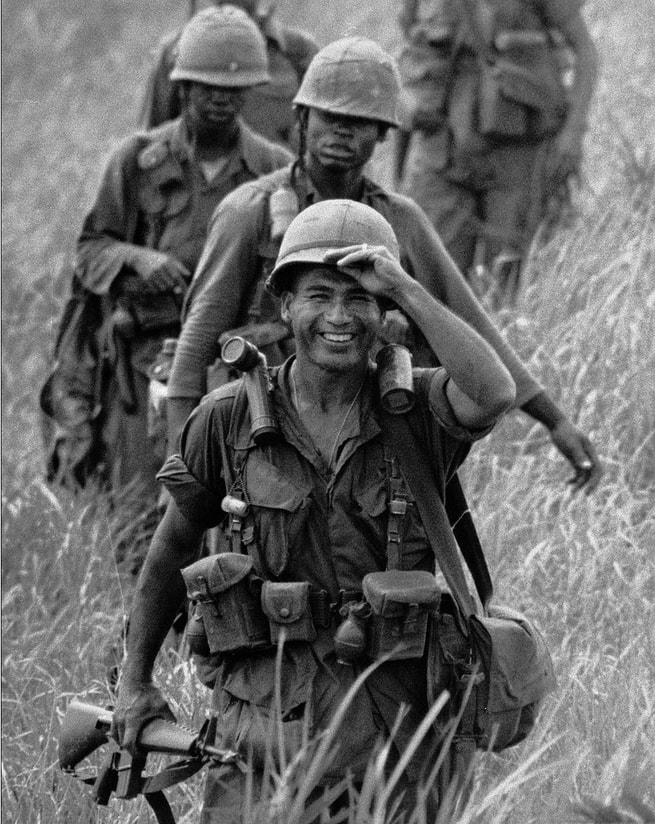

It was too late in the day to go to Personnel for in-processing, so the company clerk sent me to Supply for bedding. A member of Third Platoon showed me to my new home, a third-floor squad bay with forty bunks lining the wall on one side. In the morning someone pointed me at Personnel and I delivered my sealed records packet. To my great surprise, included in this slim stack of papers was a set of orders awarding me the Expert Infantryman Badge. The clerk helped me pin the badge, a silver flintlock on a narrow field of Infantry Blue, over my left pocket and congratulated me. As my jaw was wired shut, I could thank him only by writing on a small pad I carried. When I returned to Delta Company, I was almost immediately set upon by SFC Tabor, my new platoon sergeant. Why was I wearing the EIB? I wasn’t wearing it when I reported in! Did I have any idea what a terrible crime it was to wear an award I hadn’t earned? Writing on my pad, I asked Tabor to call Personnel to confirm. He didn’t understand why I didn’t know I’d been awarded the EIB, and I didn’t want to tell him. A week earlier at Fort Ord, California in my last week of infantry training, I went to the grenade range to throw practice grenades. They differ from the deadly variety only in that instead of four ounces of flaked TNT, they held a tiny bag of black powder, and instead of a steel plug on the bottom, a practice grenade has a cork. That day someone tampered with a practice grenade, filled it with black powder and replaced the cork with a steel plug. It exploded and split into four big fragments. I was about seventy yards away when the largest fragment hit me square in the mouth, knocking out three teeth. Hours later, after an oral surgeon had splinted two of the teeth back in place and wired my jaw shut, my company commander ordered me to remain in my quarters except for trips to the latrine and mess hall, where I could sip soup and a milkshake through a straw. I didn’t want to remain in quarters. The next day was test day. Everyone in the company and men from several other units would take sixteen different skill tests. Those who scored 75% on each of the sixteen tests would be awarded the coveted badge. Historically, less than two percent of those who took the exam won a badge. I wanted the badge, and although my head swam and I was in pain, after the company marched off that morning, I left the building, took a shortcut through the woods, and joined another unit about to be tested. I wrote on my pad and bared my teeth to show the sergeant at each test station that I would have to answer spoken questions in writing. After the last station, I ran back to the company, took a shower, and went to sleep. Two days later I was summoned to the company commander’s office. For an hour the C.O. and the first sergeant took turns chewing on my hind end. The C.O. finished by saying that under usual circumstances I would now face a court-martial, followed by a year in the stockade, followed by a dishonorable discharge, for disobeying his orders. He couldn’t do that, however, because my aggregate score on the sixteen stations was the highest ever recorded at Fort Ord, and to bring charges against me would make my C.O. look very bad and force him to answer many questions. My punishment, then, was that he, my company commander, would never award me the EIB. He handed me a trophy from the post commander commemorating my test score and threw me out the door. Four days later, when my records were unsealed at Fort Lewis, I saw that the EIB award order was signed, not by my former C.O. but by the post adjutant. I prayed that Tabor or my new C.O. wouldn’t call Fort Ord. The next day Tabor called me into his tiny cubicle in the Arms Room and said that none of his squad leaders wanted me in his squad. Was it because I was eighteen, looked fifteen, and was only an inch over five feet tall? Or that they didn’t trust me? Either way, it was an arrow through my heart. When my jaw was unwired, Tabor said, I would report to the mess sergeant for duty as a permanent KP. Until then, I would spend my time removing chewing gum from the undersides of tables in the mess hall. But I would remain with the platoon and stand all inspections. The first was the following day. I laid my unused field gear atop my bunk and arranged it, and my wall and foot lockers in accordance with the mimeographed chart provided. Tabor found no deficiencies, and when he examined the few items on my personal shelf he spent several minutes lingering over the small trophy from Fort Ord. Following inspection and lunch, we were off duty. I, however, remained in quarters because of my injury. About 2:00 pm, fully dressed and dozing atop my bunk, I was awakened by the entrance of my platoon leader, Lt. Townley. I jumped to my feet and stood at attention. Townley was a tall, slender, handsome West Pointer and an Olympic medalist in two sports. He had me sit on the edge of my bunk. He found a chair somewhere and dragged it to sit facing me. He then began to question me, in a quiet, conversational way, about all sorts of things, few of them having to do with the Army. I laboriously wrote out my answers to each question, tore off the page, and handed it to him. This went on for an hour or more. Then he got up. I got up. He extended his hand, and I shook it. He left. Monday morning my jaw wires came off. At mid-morning I reported to the mess sergeant, per Tabor’s order. The mess sergeant waved me to a chair and called Tabor. Thirty seconds on the phone and he hung up. “Tabor wants to see you in Lt. Townley’s office.” I found the office, with both Townley and Tabor in attendance. “The lieutenant and I talked it over,” began Tabor. “You are now the platoon messenger,” he said. “In the field, you will carry the lieutenant’s radios, his telephones, and a doughnut roll of wire. When we are in defensive positions, you will connect the squads to the platoon CP with telephone wire. Otherwise, you do whatever either of us tells you. Questions?” “No, sergeant,” I said. “When we are not in the field, you will clean and maintain all platoon radios, telephones, and other signaling equipment. If you need help, see the company commo sergeant. And one more thing,” Tabor continued, “Normally you would make PFC at eight months service. But all your duty was in training units. You haven’t proved yourself in a line unit. Don’t expect that stripe anytime soon.” *** Platoon messenger in a mechanized infantry unit was a tough job—at least as hard as any of the riflemen, grenadiers, or machine gunners. But it kept me in platoon headquarters in the field, six feet from the lieutenant when we were on the march and listening to the platoon and company radio nets almost 24/7. It was an education in the fine art of running an infantry platoon that I couldn’t have had any other way. The rest of the platoon, however, assumed that I was informing on them to Tabor. About two months after I arrived, I was tapped for the overnight duty of CQ runner. The Charge of Quarters was a sergeant who, when his name came up on the duty roster, took over the orderly room when the first sergeant went home to his family every night that we were in garrison. His runner ran errands, answered the phone when he was making hourly rounds after lights out at 9:00, brought midnight snacks from the mess, and whatever else he was told. In the morning I had breakfast and returned to my platoon to sleep. Before I could brush my teeth, I was told to report to the first sergeant. Top, as he was often called, said that Delta Company was required to send one man to attend the division Noncommissioned Officers Academy, a leadership course required for promotion to sergeant. Few wanted to go because it was all spit-and-polish and field exercises. “You just volunteered,” Top said. “Class starts tomorrow.” “Yes, First Sergeant,” I replied, my mind racing. “They only accept men in the rank of PFC or above,” he said and handed me a set of orders and a pair of PFC stripes. “Get those on before I change my mind,” he said. Sleep was out of the question. I was an accomplished seamster and often sewed on chevrons and patches for prices ranging from a dime to a quarter. I did so because I needed the money—of my $78 a month before taxes, $25 went home to my family, $18 went for the purchase of an obligatory US Savings Bond, and the rest didn’t stretch to cover haircuts, laundry, toothpaste, and shoe polish. I made an additional five or six dollars a month from sewing. and needed every dime. Now I needed seven more sets of PFC stripes but had no money to buy them at the PX. So I spent most of the day going around the company begging them from recently promoted specialists. A month later I returned to Delta Company wearing the rank of a specialist, my reward for finishing first in my class. The company’s senior PFCs were aghast, even after I explained that my promotion did not cost Delta any of its monthly allocations. They didn’t care. Tabor decided that I was now too senior to be the platoon messenger. He assigned me to Second Squad as the Browning Automatic Rifle gunner. The BAR weighs twice as much as the M-1 rifles everyone else in the squad carried. And I was obliged to tote twice as much ammo. I didn’t care—I was finally an infantryman. My new squad leader was Staff Sergeant Juan Cruz, a swarthy, handsome Korean War veteran and a proud Chamorro from Guam. My duties included helping Cruz do weekly inventories of the arms room and assisting him in writing semi-annual performance ratings for the rest of the squad. Although I was only a high school graduate, Tabor had decided that I had the requisite skills to pen anything and everything that SSGT Cruz needed to put in writing. Cruz was a smart guy, a gifted small-unit leader, but English was his second language. I was also the only man in the platoon who could use a typewriter. Cruz and I got along well, and after a month I handed off my BAR and became one of his two fireteam leaders. And then I came down on orders for Korea. I spent a year there, was promoted to sergeant, spent another eighteen months at Forts Benning and Jackson, and took my discharge. In 1965, certain that we were going to war in Vietnam, I re-enlisted. Three years of civilian life meant the forfeit of three stripes, and I was obliged to serve in my previous occupational specialty, infantry. Through enormous good fortune, by the end of 1965, I was in Vietnam with duty as information specialist/combat photographer with the First Air Cavalry Division. Early in 1966, Army Digest, as the service’s official magazine was then known, requested that our section provide them with images for an expansive, four-color cover story about the division and its men and machines. They sent several rolls of color film—we had none—and suddenly I was no longer the kid at the camera store who rang up film and processing purchases. I was a photojournalist on assignment for the US Army’s most prestigious publication. I made a bunch of images of our flying machines in action, then went to the field, looking for shots of men at war. One afternoon I hopped off a helicopter and looked around the landing zone. In the distance, a column of troops made their way downhill through thick elephant grass. I chose my borrowed 300 mm telephoto, turned the image into a vertical, and waited until the man at the head of the column swam into focus. Sergeant First Class Cruz recognized me. As I gently released the shutter, he smiled. Decades after that image appeared in Army Digest, his daughter became a Facebook friend. © 2018 Marvin J. Wolf

2 Comments

|

FROM Marvin J. Wolf

On this page are true stories, magazine articles, excerpts from books and unpublished works, short fiction, and photographs, each offering a glimpse of my life, work and times. Your comments welcome. © Marvin J. Wolf. All rights reserved. Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

|

|

Member, Military Writers of America

|

Website © 2016 Marvin J. Wolf. All rights reserved on website design, images and text. ꟾ Updated regularly.

Design by Andesign. |

Professional Reader, NetGalley

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed