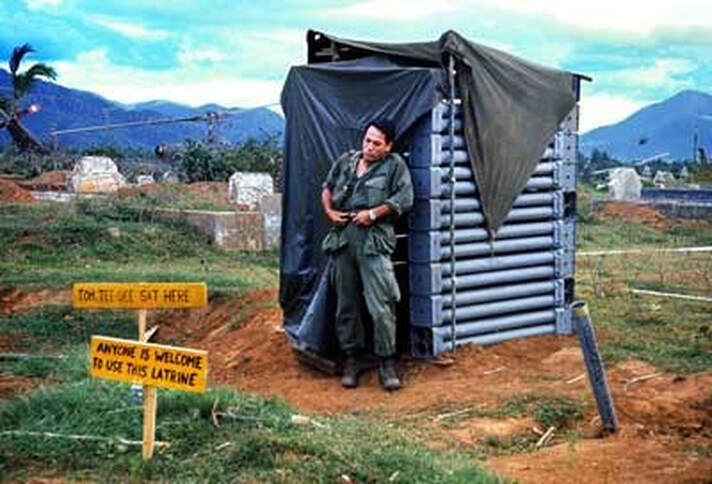

I Didn’t Set out to Be in Nonprofit Black Market Supply With Whiskey as CurrencyI steered the jeep off the dusty, rutted main road and rattled down a well-worn track until I beheld a bizarre juxtaposition of images: the silhouette of a thousand-year-old Hindu temple cheek by jowl with something resembling a porcupine dozing on a glass box—an air traffic control tower bristling with radio antennae. Standing nearby, as expected, was a 30ish man, perspiration staining the armpits of his blue suit, a wilted tie drooping across a damp shirt that had until recently been starched and white. A few minutes of morning sun had turned his face and neck bright red. He wore checked socks and new penny loafers that looked like they might come apart at the seams momentarily. A reporter for one of the larger Midwest dailies, he’d arrived in Vietnam so recently that he was still peeing stateside water. At his first Saigon stop, the Associated Press office, he’d received a brief orientation... Read the full story I wrote for The War Horse © October 2023 Marvin J. Wolf. All rights reserved. #Vietnam #VietnamStories #foodies ##blackmarket #latrine #memoirs #MajCharlesSiler #VietnamWar

0 Comments

|

FROM Marvin J. Wolf

On this page are true stories, magazine articles, excerpts from books and unpublished works, short fiction, and photographs, each offering a glimpse of my life, work and times. Your comments welcome. © Marvin J. Wolf. All rights reserved. Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

|

|

Member, Military Writers of America

|

Website © 2016 Marvin J. Wolf. All rights reserved on website design, images and text. ꟾ Updated regularly.

Design by Andesign. |

Professional Reader, NetGalley

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed